By Paul Rozycki

Editor’s Note: This story was updated Sept. 3 to clarify that the C.S. Mott Foundation, in the fourth year of its five-year $100 million water crisis commitment, has awarded $93.5 million. East Village Magazine’s Mott Foundation grant is separate from that commitment. Also, we have clarified that over the last decades the Ruth Mott Foundation has paid out between $4 million and $7 million annually in grants to Flint groups and organizations.

The city of Flint is now in the midst of a competitive campaign, and by all indications it looks to be a hard-fought contest to choose the next mayor. We will hear much from both Mayor Karen Weaver, and her challenger, Sheldon Neeley, about their plans for the city as both campaigns move toward the Nov. 5 general election.

Meanwhile, the City Council continues with its marathon meetings as they bicker, battle, and try to recall each other, to the great frustration of anyone trying to cover them, as well as most citizens.

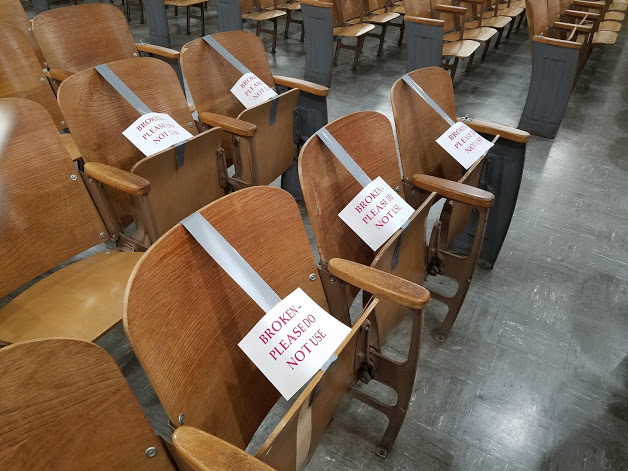

Broken chairs in the City Council chambers (Photo by Tom Travis)

Flint citizens have spent much time and energy passing a new city charter, trying to implement it, and arguing about why it’s taking so much time.

For all the attention that we give to what happens in City Hall, maybe we’re looking in the wrong direction.

Maybe the events in City Hall don’t matter as much as we think they do.

Maybe the real future of Flint rests in hands that don’t get as much attention, and don’t face the voters.

At least that’s one argument being made about cities like Flint.

“Governing without Government”

A few months ago, a paper titled “Governing without Government:Nonprofit Governance in Detroit and Flint” was published by Sarah Reckhow, associate professor of political science at Michigan State University, Davia Downey, Grand Valley State University, and Josh Sapotichne, also of MSU. Their main point was cities that have faced a dramatic decline in their ability to govern themselves —either because of their lack of resources, or their own ineptitude —often end up being governed, not by elected officials, but by non-profit foundations, who play major roles in addressing the cities’ problems and crises.

While many Midwestern cities are facing declines in population and resources, Reckhow and her colleagues offered two Michigan cities as prime examples of how non-profit foundations have eclipsed elected governments, as those governments declined in their ability to respond to public needs. Those two examples were Detroit and Flint.

The paper highlighted Detroit’s dramatic decline in population (29 percent) and its even greater decline in its city employees (50 percent). Yet, as bad asDetroit’s problems were, Flint’s were worse.

The authors said,“Yet, the most striking feature of this analysis is that even after observing Detroit’s dramatic decline in government workforce, things look worse in Flint … Flint lost 22 percent of its population between 2000 and 2016 —from about 125,000 residents in 2000 to just over 97,000 in 2016. Over the same period, the city government lost 56 percent of its workforce —from nearly 1,100 full-time employees (FTEs)in 2003 to 473 in 2016.”

As Detroit and Flint faced declining populations and reduced resources, they each dealt with a major crisis — the Detroit bankruptcy, and the Flint water crisis. Both of those events brought non-profit foundations to the forefront in response.

Foundations step in

In both cases, the cities increasingly relied on non-profit foundations to offer solutions that the governments couldn’t. However,as Detroit and Flint dealt with their problems, the public response to the foundations, and their city governments, was strikingly different. In Detroit, after their bankruptcy, and the “Grand Bargain” that resolved it, the City of Detroit government was still ranked as the “most important community leader.” Itwas followed by the Detroit Land Bank Authority, the Kresge Foundation, the Community Foundation of SE Michigan, the Skillman Foundation, and the United Way of SE Michigan. The authors felt that those foundations played a major role in the revitalization of Detroit’s local government.

However, in Flint, a very different pattern emerged. When asked who was the “most important community leader,” Flint residents ranked the United Way of Greater Flint in first place, followed by the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, the C.S. Mott Foundation, the Food Bank of Eastern Michigan, andthe Red Cross. In the Flint survey, the City of Flint government came in last. In Flint, the authors felt that foundations might become a more permanent fixture, as the city government struggled to become more effective.

In Flint, these results may reflect both the leadership and financial ability of our local foundations, as well as the weaknesses of our city government and its resources. Given the history of Flint, it’s no surprise that the Mott Foundation, the Community Foundation, and others have all played major roles for years, long before the water crisis.

Major foundations in Flint and Genesee County

At a recent open house, the leaders of the Community Foundation for Greater Flint presented an outline of the range and reach of one of the major foundations in the Flint area. The Community Foundation grew out of a merger between the Flint Public Trust and the Flint Area Health Foundation in 1988. A full review of the foundation’s activities is impossible to cover in a brief column, but since that time they have seen their assets grow to more than $262 million and have received support from more than 19,000 donors. They have awarded more than $130 million in grants in Flint and Genesee County and are playing a major role in the Flint water crisis. They administer more than 750 charitable funds and planned gifts from supporters.

At a recent open house, the leaders of the Community Foundation for Greater Flint presented an outline of the range and reach of one of the major foundations in the Flint area. The Community Foundation grew out of a merger between the Flint Public Trust and the Flint Area Health Foundation in 1988. A full review of the foundation’s activities is impossible to cover in a brief column, but since that time they have seen their assets grow to more than $262 million and have received support from more than 19,000 donors. They have awarded more than $130 million in grants in Flint and Genesee County and are playing a major role in the Flint water crisis. They administer more than 750 charitable funds and planned gifts from supporters.

The C.S. Mott Foundation and the Ruth Mott Foundation are even better known in Flint. Founded in 1926, the C.S. Mott Foundation has grown from an initial $320,000 endowment to more than $3 billion today, and has given grants worth more than $3.2 billion in 62 countries. A full listing of its activities and philanthropy is extensive and far-reaching, but for the Flint area, in the fourth year of its five-year $100 million commitment, it has awarded $93.5 million in area grants.

The C.S. Mott Foundation and the Ruth Mott Foundation are even better known in Flint. Founded in 1926, the C.S. Mott Foundation has grown from an initial $320,000 endowment to more than $3 billion today, and has given grants worth more than $3.2 billion in 62 countries. A full listing of its activities and philanthropy is extensive and far-reaching, but for the Flint area, in the fourth year of its five-year $100 million commitment, it has awarded $93.5 million in area grants.

East Village Magazine is a recipient of a Mott Foundation grant, separate from the $100 million water crisis commitment.

Similarly, in the last decade, the Ruth Mott Foundation has paid out between $4 million and $7 million annually in grants to Flint groups and organizations, with a particular focus on the north end of Flint.

United Way of Greater Flint and Shiawassee counties has allocated over $3 million for local programs and leveraged more than $15 million from other matching sources.

Those are only a few of the major foundations that play a major role in Flint and its development. There are many others with similar numbers, and similar programs, who contributed to addressing Flint’s problems and concerns with their philanthropy.

Taken together, the foundations and non-profits may play a bigger role in our future than the city government, with its $55 million budget.

What does it mean for Flint?

There is no doubt that the residents of Flint should be thankful for the role that foundations have played in the life of the city, not just during the water crisis, but for much of the last century. Flint wouldn’t be the same without them.

On the other hand, as Reckhow’s paper points out, what does this mean for democracy, when the elected officials are marginalized, either through lack of resources or their own conflicts? While we should be grateful for the contributions of the foundations and all they have done, they can’t do this forever. Atsome point the city must become self-sustaining, and can’t endlessly rely on grants and non-profits to replace elected governments.

The limits of foundations

And for all they accomplish, foundations and non-profits have their limits. At the conclusion of her paper Reckhow says,“Although local government control has been restored in both Detroit and Flint, and capacity has improved in Detroit, residents in these cities may have concerns about transparency in governance and capacity, as nonprofits are driven to do more public service provision in place of the local government unit. Nonprofits, while mission driven, do have significant barriers to entry in serving large populations. When nonprofits are focused on particular services they tend to excel; however, unlike their local government counterparts, nonprofits have the luxury of being selective when providing services. In the case of local government units, city officials are statutorily obligated to provide for all citizens within city limits, not just those who meet certain criteria.”

Paul Rozycki (Photo by Nancy Rozycki)

Flint may be one of the prime examples of non-profits filling the gap when governments can’t deliver, but it’s not alone. Many other industrial citiesface similar difficulties. Clearly,state policy needs to invest more in developing and supporting local governments, particularly those facing declining populations, outdated infrastructure, high legacy costs, and shrinking tax revenue.

In the long run, that may build the strongest foundation for any city.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated Sept. 3 to clarify that the C.S. Mott Foundation, in the fourth year of its $100 million water crisis commitment, has awarded $93.5 million. East Village Magazine’s Mott Foundation grant is separate from that commitment.

This story was updated Sept. 4 to clarify that the Ruth Mott Foundation has paid out between $4 million and $7 million annually in grants to Flint groups and organizations, with a particular focus on the north end of Flint.

EVM political commentator Paul Rozycki can be reached at paul.rozycki@mcc.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.